|

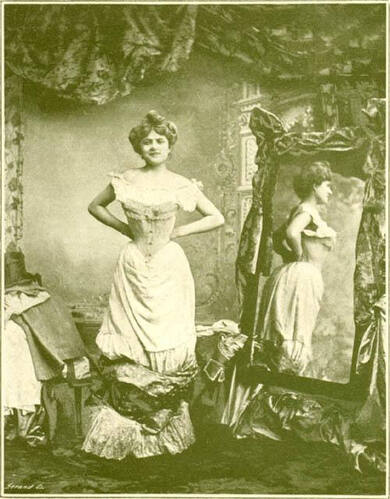

Another year is already coming to a close! I've been working on this guide to Edwardian lingerie on and off for several weeks, and have finally managed to pull it all together in one article. So here is my detailed survey of Edwardian lingerie -- what to wear and how to wear it. I hope it will answer all those questions about the unmentionables of this era, and be enjoyable too! It's quite a long article, but you can scroll through to whatever most interests you (click on the title above, or on "Read More", to access the article). By the way, you can find the 'History House' sewing patterns of a number of the items featured in this article at the link below. Of all the costume eras I’ve studied, none seems to have been more focused on making supremely beautiful things that were essentially invisible than the Edwardian period. There was a truly staggering variety in the qualities, designs and types of lingerie available during that time, not to mention the sheer quantity of undergarments available. For the first time in history, women’s underthings (including corsets) were being mass-produced in factories and offered (often in mail-order catalogues and the new “department stores”) on a scale never seen before. And many of those offerings were of a beauty of construction and complexity that almost defies imagination. Often the required set of fine Edwardian lingerie cost more than the outer dress or gown itself. First, I should clarify that what I mean by the “Edwardian era”. In this context, I’m referring to the time period from about 1898 or 1899 to about 1918. The reason for this spread (which some might find unusual) is clear in my view. Although it's true that King Edward VII only reigned from 1901 to 1910, the aesthetic of dress remained more or less consistent from 1898 to 1918 (and possibly further), even as modernism was chipping away at the edges. WWI itself (1914-18) didn’t instantly and completely destroy the modes and expectations of Edwardian dress. However, so much changed in both society and fashion after 1918 that the design and construction of lingerie became different and simpler in a way that never looked back. Not only were the masses of young, female (mostly immigrant) factory workers no longer available to create stunningly intricate undergarments at near-starvation wages, but undergarments themselves no longer served the exalted function they once had done. By the 1920’s lingerie had for the most part become utilitarian underwear. Accordingly, for this article, the term “Edwardian” should be understood as generally applying to the whole period of 1898 to 1918, and perhaps even 1919/1920. PART ONE: What Was Worn When, and How Was It Worn? It’s no wonder, given the plethora of lingerie available during the Edwardian period, that people attempting to re-create an Edwardian ensemble may have difficulty understanding exactly what was worn, and how it was worn. I’m often asked: “What exactly should I wear under this gown?” While it’s important to know the various components of undergarments of this era, it’s also essential to appreciate that fine lingerie from about 1898 to about 1919, while still remaining fairly consistent in type, did change in cut and silhouette. As a result, it’s essential to have the right undergarments for the year that your outer garments are portraying. Generally speaking there was an overlap in lingerie from one year to the next, which means that some styles can reasonably be worn to portray several years. Other years marked a relatively quick change in fashions and silhouette. So for example, a petticoat of 1901 can be worn pretty much up to about 1910, but by 1911 you should be thinking about a different, slimmer, more columnar style. Keep in mind as you read the descriptions in this article that the specific type of undergarment worn in this era was often based on age. A mature woman of 45, for example, in 1906, would be unlikely to wear the newest “combinations” with her dressy gowns that her 20 year-old daughter might happily adopt. Older women tended to continue to stick to their traditional, classic 4-piece Edwardian set of underthings even into the late 1910’s and early 1920’s, until fashion changed so dramatically and hems rose far enough that the old layers of flouncy lingerie simply no longer made any sense. For the purposes of this article, I’ll put aside the fascinating social and psychological discussion of why such beautiful but hidden garments existed in the first place, and deal with the practicalities of what they were and how they were worn. My main purpose, based on decades of research and making replica historical garments, is to provide some guidance on what lingerie to make and wear under which types of Edwardian reproduction garments. First, it’s important to realize that, although there was an entire range of quality in undergarments available during this period (everything from the sturdy, plain and serviceable to the frothy, diaphanous and lacy), what women most desired and aspired to if they could afford it were the fine, delicate, lace-encrusted pieces promoted by advertisements and fashion sketches in ladies’ magazines of the time. The epitome of this luxe were the trousseaux, or fine sets of lingerie, usually consisting of pieces with matching lace designs. Delicate, semi-sheer cotton batiste or finest lawn, with beautiful Valenciennes laces (sometimes hand-made) were the preferred materials, although taffetas and other crisp fabrics were often used for petticoats, especially those intended as the outermost layer of lingerie, or underskirt. In short, this was the lingerie every woman wished for and purchased if she was able to do so. Accordingly, I’ll be focusing on these types primarily. Despite their beauty and complexity, well-made, fine quality lingerie was widely available during the Edwardian years, even through mail-order, and was well within the reach of middle-class purses (for reasons to do with the use of cheap labour in big factories, a subject beyond the scope of this article). The fact that so many of these pieces still exist on the open market today is a testament to their pervasiveness 100 years ago. To start from the inside, and work out then, here is an outline of the classic pieces that were typically part of the well-dressed woman’s wardrobe, and how they should be worn. I’ve also included notes on the changes to these pieces (if any) though the time period in question. Further on I'll provide some complete wardrobe examples of which pieces to wear with which dresses in particular years throughout the Edwardian era. 1. The Chemise No self-respecting woman of the Edwardian era would be dressed without first donning a chemise. Although the chemise had the primary practical purpose of protecting the corset from direct contact with the body, and wicking away moisture from the skin, it also played the secondary role of helping to keep the flesh of the bosom above the top of the corset properly arranged, and being the first line of defence of modesty below the waist. This was especially important when fine, semi-sheer outer dresses were worn (the fashionable so-called “lingerie dresses”). Quality chemises of this period were relatively shapeless garments, but were almost always lavished with Valenciennes lace insertion and edging at the top. The variety in decoration was staggering. Chemises intended for wear under evening or ball gowns often had shoulder straps made of simple silk satin ribbons, which could be adjusted or pushed down off the shoulders as preferred, so as not to be visible under a gown with a décolleté neckline. Chemises came in various neckline configurations, some of them with a square opening to match the outer garment (especially in summer). Length varied, but most were generally somewhere around or just below knee length. Since they were worn next to the skin, chemises typically were made with less all-over lace insertion than the other pieces of lingerie, to make them stand up better to repeated washing. Most of the better quality chemises had decorative coloured silk ribbon run through lace beading around the neckline, to allow the neckline to be adjusted to the wearer's preference. This ribbon would be removed when the garment was laundered and replaced afterward. Women who could afford it had a number of chemises, laundered, pressed and ready to be changed into day by day. There are accounts of wealthy women purchasing dozens of them at a time. Interestingly, despite being so ubiquitous during the Edwardian era, few chemises of this period come onto the open market today for sale (unlike petticoats and corset-covers). We can only speculate that most either wore out or were discarded. Changes over time: The chemise itself changed very little throughout the Edwardian period. However, some women (especially younger women and later in the era) wore an undergarment which combined the chemise and drawers in one piece, called a “combination” (which I’ll discuss further on). How to Wear: The chemise is put on over the head, the neckline ribbon pulled up and tied in a bow at front, and the garment arranged more or less evenly around the body (before the corset is put on). Once the corset is on, the front of the chemise can be pulled downward to hold the bust in place above the top of the corset. Chemises were not, as a rule, shown on their own on female bodies in advertisements or fashion sketches of the time, unless a corset was shown over them, so images of them in their entirety on a model are very rare. But we can see the beautiful, lacy construction of these garments peeking out from corset tops in many fashion sketches of the time, as in the examples below. I’ve studied many hundreds of these, and find the variety of lace design and arrangement in these otherwise simple garments astounding. Another source of information about chemises and how they were worn were the “racy” postcards of the era, although from the point of view of costume history, we should assume there is an element of exaggeration in these, as in the high-fashion sketches of the day. Here are some examples of images of the time period that show chemises being worn (under their corsets): 2. Drawers (aka “Knickers” or Pantaloons) By the late 1890’s fashionable drawers, the most "unmentionable" of hidden lingerie, had gone from plain, utilitarian Victorian pieces made of sturdy, no-nonsense cottons to delicate and flouncy confections made of the finest semi-sheer batistes and lawns or fine silks, embellished with laces. Fancy drawers of the Edwardian era consisted of two separate, widely-flounced leg pieces, constructed identically and joined at the front but open through the crotch area (so-called “open drawers”). Most fastened at back, typically with small mother-of-pearl buttons, and were adjusted with a narrow waist tie run through the casing/waistband around the top of the drawers. Fully “closed” drawers were unusual during this period.

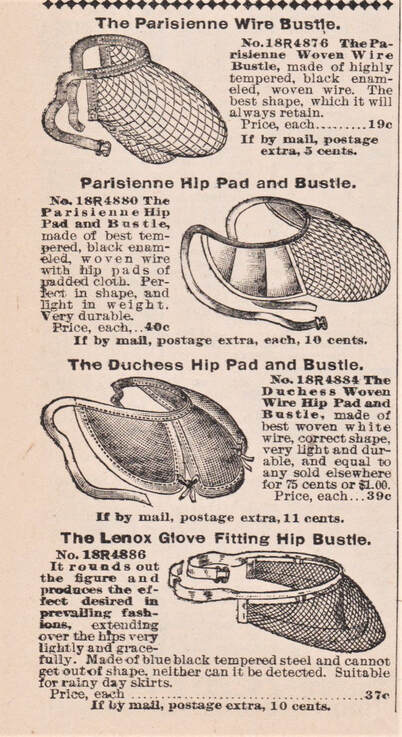

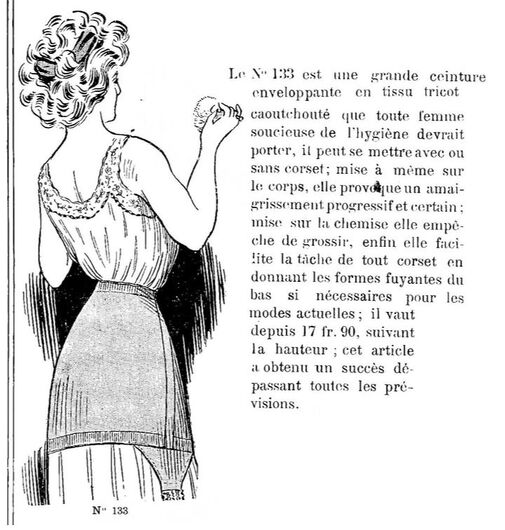

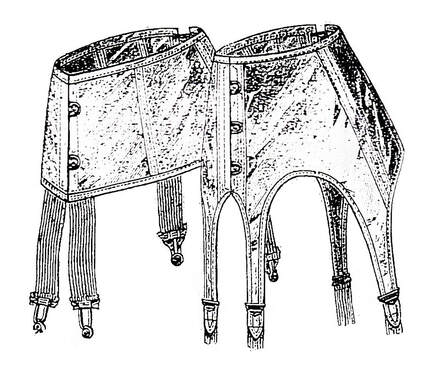

There were drawers with narrower legs as well, even during the early part of the Edwardian era, but these tended to be worn in summer, or with informal daywear, and more often by younger women than older. For evening wear, flared and flounced drawers were typical up to about 1910-12, usually made of the finest, most lightweight and diaphanous batiste, lawn, or (less often) lightweight silk, which minimized bulk above the hip area. The drawers, in addition to providing a necessary layer of modesty, also served (especially in the early years of the Edwardian era) to add loft and shape to the outer garments. The classic drawers of the early period were rather long (around knee-length or longer), and cut with wide, flared legs, typically ending in even wider frills or flounces, embellished generously with lace. They were very pretty things! Changes with Time: After about 1910, when more columnar outer silhouettes became the rule, fashionable drawers tended to have narrower legs, even for evening wear. Toward 1912 and especially later, fairly slim, one-piece “combinations”, replacing chemise and drawers, became more and more popular as the slim silhouette of outer garments no longer required the extra loft provided by chemise plus drawers. The “combinations” also made it easier to smoothly attach the number of hose supporters (garters) that later corsets often included. (See my discussion on these 'combinations' further on). How to Wear: Drawers were usually worn under the corset and chemise. The reason for this was that hose-garters attached to the corset (which became common during this era) could then be passed over top of the drawers/chemise and fastened to the stocking tops. This allowed the garters to be more easily accessed and adjusted. This arrangement can be seen in fashion sketches and “racy” postcards of the era. It did produce a rather “bunched-up” effect, but this actually helped to puff out and give shape to the below-hip area of the widely flared skirts and dresses of 1901-08. The drawers were stepped into, pulled up to the waist (under the chemise), then the buttons at back fastened. Most of the material was drawn up toward the back by means of the adjusting ties, which were then tied in a bow at centre back. This was a key feature: the cut of Edwardian drawers was such that the front portion fit smoothly over the abdomen and hips, while the back, being much looser and wider, was pulled up into close gathers with the ties. These gathers created some of the semi-bustle shaping that helped produce the iconic S-curve silhouette. For corsets without garters, the drawers could be worn over the corset, but this wasn’t a typical arrangement at the time. Here are a few images, including some from "naughty" postcards of the time which give an idea of the array of styles and trimmings lavished on drawers. These types of postcards give fashion historians today some of the few real glimpses of how undergarments may have been worn. Incidentally, for anyone curious about the French caption, I'll translate: "Beauty Contest -- We have some for every taste; They are not made of rubber" (referring to the breasts of course, but a play on the fact that some lingerie of the time -- especially bust improvers -- were advertised as having some rubberized components). The little rhyme has a much more amusing effect in French! 3. The ‘Combination’ (Chemise + Drawers) While the classic first pieces of lingerie put on were the chemise and drawers, the “combination” was an alternative, particularly for ordinary, informal day wear and sports-wear (such as that term was understood at the time). This was a one-piece undergarment replacing the chemise and drawers, but with similar construction to the separate pieces. It can be thought of as a chemise attached to a set of drawers at the waist, sometimes without a waistline seam, usually front fastening with little mother-of-pearl buttons. In the early Edwardian years, these (like drawers) were usually "open" style, i.e. not fully sewn around the crotch seam. This concept, of turning the chemise and drawers into one undergarment to be worn under the corset, had been around for a very long time, at least since the early 1870’s. But Edwardian designers transformed this item, like all the others, into a delicate fantasy of frou-frou. Generally speaking, “combination” chemise+drawers were preferred by younger women, but were not considered appropriate to wear with evening dress. Mature and older women tended to stick to the traditional, separate chemise and drawers. Changes Over Time: The earlier “combinations”, especially ca. 1902-06, usually had wide, frilly, legs just like their separate counterparts. The later models (after about 1910) frequently had slimmer, more closely-fitting legs. Throughout the entire period, plain, practical “combinations” made of fine, closely-fitting knitted material also existed (sometimes referred to as “union suits” or “turnbulls”), meant for warmth in cold seasons. Until about the mid-1910’s, combinations were usually (although not exclusively) made with “open” drawers, but in later years, after about 1915, buttons or snaps were added to close the crotch seam. These were sometimes referred to as “envelope chemises”. By the 1920’s, these undergarments had evolved into what we think of as “teddies” or “onesies”, a simple, straight, sleeveless one-piece top with fairly straight legs that slipped over the head and was snap-fastened at the crotch. Here are a few more examples of this two-in-one undergarment: How to Wear: Wearing a “combination” of this type is simple – step into the legs, pull the combination up so the top straps are on your shoulders, do up the front buttons, adjust the neckline with the ribbon (as for the chemise), adjust the waistline ribbon (if any), and then put on your corset. Above are a few examples of these undergarments from various sources. 4. Bust Improvers, Bust Supports (Brassières) and Bust Padding: These undergarments were common during the Edwardian period, particularly for women who were less than fashionably endowed in the bust area, to create a more ideal “S-Bend”, uni-bust or pigeon-breasted silhouette. The design and shape of these garments varied enormously, but most were made of cotton (such as percale or batiste), with more or less boning, had shoulder straps of one kind or another, and could be back or front fastening (or rarely with a laced closure, as shown below). Some models, both the brassière types and the boned corset-cover types, had an elasticized suspender at lower front which fastened over one of the corset studs or bottom buttons. The construction, cut, and arrangement of all of these "shaping" undergarments varied widely throughout the Edwardian era. How to Wear: In the earlier part of the Edwardian era, bust improvers were worn either under or over the corset, but always under the corset-cover. Some were so firmly boned and shaped, they were advertised as being able to be worn without a corset. Later designs (toward 1914 and onward) were often constructed much like a corset-cover, but with boning, and were worn in place of the corset-cover. A “brassière” of the 1900-1918 era (see description following) would usually be worn over the corset as shown in the 1913 sketch below, and a corset-cover (or ‘combination’ corset-cover/petticoat) would be worn over top of the brassière. I have never seen any lingerie sketches of this period showing a boned bust improver and a “brassière” being worn at the same time. It’s reasonable to assume that where these pieces of lingerie are concerned, you should decide to wear one or the other. However, a boned corset-cover (such as the 1917 type shown below) could logically be worn over a corset-plus-“brassière” to give additional loft and shape to the bust area. Changes over Time: After about 1906, we see both bust improvers (usually in the guise of a boned corset-cover), and the simpler “brassière” type, a shorter, slightly, less structural garment with shoulder straps, with or without boning. This latter undergarment had been around for some years, but did not really become common until after 1910-12. These “brassières” were originally worn over the corset, and later were worn more as a bust supporter over the area just above the low-line, under-bust corsets of 1913-19. In this sense, the earlier, firmly shaped and boned bust improver (or the boned corset-cover) served a different purpose from the “brassière”, which was primarily intended to give support to the breasts. These of course later evolved into what we today know of as a "bra". As the fashionable "uni-bust" or "pigeon-breasted" silhouette of the early years of the Edwardian era faded after about 1913, bust improvers in the exaggerated larger shapes disappeared as a component of regular lingerie, replaced by boned or ruffled corset-covers, or “brassières” (boned or unboned). The latter were called "soutien-gorge" in French ("bust support") . Bust pads, as such (which were used especially in the earlier years of the period) were simply slipped into the inside of the corset, or sewn to the inside of bodices, especially into dressier day gowns and evening and wedding gowns. Below are a number of examples of bust improvers (enhancers), bust supporters, boned corset-covers intended as bust enhancers, and simple bust-pads, from various original sources from about 1902 through 1917. This is just a snapshot of the variety available during this period. In the later years of the Edwardian era, it's sometimes difficult to say whether one of these garments is intended as a supporter or enhancer, especially where the boned corset-covers are concerned. They probably served both roles. 5. The Corset: Although the corset is the essential structural undergarment of the Edwardian era, I consider it to be in a different category from lingerie per se. Accordingly, I won’t go into any details about the garment itself, except to say that the Edwardian corset existed in an incredible variety of styles, materials and finishes, to suit almost every occasion, taste and budget. The typical Edwardian corset was an under-bust type (in the sense that it supported the bust up to about nipple level), was always worn over a chemise, and fastened at front with a steel busk. Over-bust corsets (that is, corsets that curved up over the bust) did exist, but were far less common. Button fastening corsets were also made, but these were mostly used for outdoor, sport, or specialty purposes. Although everyday corsets of this period were often made of sturdy, serviceable cottons like coutil or cotton jean, dressier Edwardian corsets (and summer types) were very often constructed of far lighter materials than might be assumed today. Corsets of cotton batiste, silk satin and lightweight brocades were common, as were corsets made of open net material. Later in the era, rubberized, stretchy, or tricot (finely knitted) corsets became available. The dressier or more formal the ensemble and the more expensive the lingerie, the finer quality corset a woman would want to wear. Full steel boning throughout corsets was not the rule during this era, although the very fronts and backs tended to be more strongly boned with steel. Whalebone (baleen) was still used in most corsets of this era, especially those made in Europe. Spiral boning and aluminum boning was only commonly available in corsets after about 1912. Changes with Time: Until about 1910, corsets of this era were the straight-front style, which created a strong, straight line at front, tipping the bust forward and tending to force the hips outward at back, creating the iconic “S-bend” silhouette. After this point (that is, sometime around 1910), with the advent of the new “columnar” styles, the fashionable corset was longer, with less structural shaping and more evenly-distributed vertical boning around the torso. How to Wear: There have been volumes of text written about how to wear and adjust a corset, and myriad arguments over the health issues of wearing a corset, which I won’t attempt to summarize here. Suffice it to say that your Edwardian corset should be well fitted to your personal body shape and measurements, and should, if properly designed, not be uncomfortable (let alone painful) to wear in normal standing or sitting positions. The corset is always put on over the chemise, after first loosening the back lacing and unfastening the busk. A helper is really a necessity for this process. Fasten the busk, then have the helper slowly and evenly pull up the lacing until the corset feels very snug. While the helper is pulling up the laces, arrange the bust comfortably and pull down gently on the chemise to help keep the flesh of the upper bust in place. Fastening the corset lacing can either be done by working from top to bottom, or, as was sometimes the case, in a method called in French at the time “à la parasseuse” (lazy-woman’s style). This involved tying the laces securely at bottom, then grasping the ends in the middle just slightly below waist level and tightening from top and from bottom, creating the so-called “rabbit-ears” at centre back, which are then tied in a tight bow. This method can be adapted to be done by the wearer herself. The one problem with this procedure is that it does create some extra bulk at the back waist area, with the four ends of the lacing all tied together. Once the corset is on and the initial adjustment is done, wait quietly about 20 minutes. You’ll find that the body will adapt to the corset (the lower ribs will have bent inward), breathing will seem easier, and the corset may be able to be further tightened through the waist area. 6. Hip Pads and Bustle Pads: These lingerie accessories were sold as rather small, wire mesh and/or stuffed fabric poufs shaped somewhat like rounded clamshells. They were intended to protrude from around the upper derrière and hip area to fill out the deficient figure, and were usually fitted with straps that tied around the waist. It’s difficult to say exactly how widespread the use of these undergarments was. There has been much discussion and many assumptions on the subject, but my view, gleaned from researching sources of the era, is that their use was less widespread and general than many people these days claim. My opinion is based on three main observations:

My conclusion is that, unless a woman's proportions were ill-suited to achieve the S-bend silhouette of the ca. 1901-09 era by means of the usual lingerie, bustle pads were an unnecessary addition. The Edwardian aesthetic favoured balance and elegance in the figure. The bustle pad, and to some extent the bust improver, was available to enhance what might be naturally lacking, rather than to create an exaggerated, even potentially comical, silhouette. Edwardian hip padding or 'bustles' were in any case not meant to create an actual bustle shape along the lines of the 1870’s or 1880’s, but rather to fill out the figure gracefully in the fashionable, so-called "S-bend" line. Changes over Time: After about 1908, fashions changed significantly with the more sinuous lines of 1909, and the columnar dresses of 1910-14. Hip padding was no longer necessary or appropriate for these later styles. Even toward 1915-16, when skirts again became much wider, hip padding was no longer used. How to Wear: Today, where women’s waists have not been corset-trained from a young age to the typical waist sizes of the Edwardian era, if you are planning to wear a reproduction garment of about 1901-07, some padding may help to increase the bust-to-waist and hip-to-waist proportions, producing more of an hourglass illusion. However if you are wearing a dress or gown later than 1909, hip pads are not appropriate. Even if you are going to be wearing a “Gibson Girl”, S-bend style gown of the 1901-07 era and want to accentuate the silhouette, be cautious about how much padding you add, to avoid looking like a caricature. Unlike some earlier periods (such as the late 18th Century) where padding was a necessary adjunct to a costume, padding in the Edwardian era was done judiciously and as inconspicuously, to make up for figure deficits and create an elegant, supple appearance. Hip pads could be worn over the chemise and under the corset (depending on the shape and cut of the corset), but it was more usual to wear them tied in place at or just below the waistline, around the outside of the corset. 7. The Petticoat: This is the piece of lingerie for which the most extravagant embellishment, flouncing, and frou-frou was reserved. The Edwardian petticoat, up to about 1917, was almost always cut in the same way, with a smooth, moderately slim A-line centre panel, slightly more flared but still smooth side gores, and wide, often rectangular back sections. These back sections were meant to be pulled up into close gathers with the adjusting ties (as with the drawers), providing a soft “loft” effect at the upper back of skirts and gowns. In addition to the adjusting ties, petticoats of this era generally closed at back with several buttons (usually mother-of-pearl in the better pieces). Edwardian corsets, especially European designs, were sometimes equipped with upside-down hooks at front, positioned slightly off-centre and below waist level. These were used to hold the front edge of the petticoat waistband down, minimizing bulkiness around the waistline and helping to accentuate the straight-front, S-bend line. In the late Edwardian era these hooks tended to be simply large, plain hooks, but Edwardian corset-makers turned even that small accessory into an art form, creating them as long, flat, dagger-shaped additions, often with a decorative embossed or engraved surface. These hooks persisted on corsets up to 1912-14, but were uncommon later. For Edwardian reproduction wear, these hooks work best with lightweight petticoats, otherwise unattractive bumps and ridges can show through outer garments. It is still possible today to have a reproduction corset made with these hooks added. Personally though I feel the effectiveness of such a hook in minimizing bulk is dubious if you're wearing a fine, lightweight batiste petticoat. Below are some examples of these types of hooks on extant corsets and in "racy" postcard photos of the era, showing them in actual use: The overall effect of petticoat design, as with the drawers, was to produce a straight, smooth appearance at the front of a costume, with the gathers at back helping to fill out the semi-bustle silhouette. In fact, in my experience working with original sewing patterns of this period, it was almost universally the case that the back gore(s) of skirts were cut slightly longer than the front (usually about 2.5 to 3.0cm [1 to 1-1/4”), even for skirts meant to be street-length all around. The reason for this was to allow for the extra length that would be taken up by the back “padding” effect of the drawers and petticoat. It’s important to understand however that this extra padding was not intended to create a true bustle shape (as in the dresses of the 1870’s or 1880’s), but to softly enhance the silhouette and provide more loft and shape at the back of dresses and skirts. This was the case even as late as 1912. In the first few years of the 20th Century, fashionable petticoats came in a wide range of materials and colours, including various cottons, silks, and plain or plaid silk taffeta, which was very popular up to about 1906 (and after 1914). Mail-order houses offered petticoats in a huge array of styles, colours, and fabrics, including some “faux” silks (probably made of some type of cotton in the early years, then later rayon). There was something for every budget. However, the most expensive and desirable petticoats of the time were made of exquisitely fine, semi-sheer batiste and lawn, trimmed with delicate Valenciennes laces and silk satin ribbons. Silk taffeta was especially popular for petticoats during the first few years of the 1900’s to give extra loft to the wide skirts. Taffeta petticoats were also again fashionable during 1915-16 when skirts were again cut with very wide, or flounced gores (even though a little shorter). However, during all these years, petticoats of fine batiste, embellished with laces, continued to be very common. Often, during about 1900-1908 and again in 1915-16, a beautiful silk taffeta petticoat would be worn over another, lighter cotton batiste petticoat. These fancy taffeta types were sometimes referred to as “underskirts” or simply “skirts” at the time. For evening, petticoats were even more lavishly cut and decorated. Their flounced bottom edges were intended to bounce outward, providing a tantalizing glimpse now and then during dancing or walking, making them the only (slightly) visible part of the whole set of underclothing. Changes over Time: The era of the most luxurious, full, extravagant petticoats was about 1898 through about 1908/09, many in silk taffeta of one kind or another for the cooler seasons, especially striped and plaid, and otherwise preferably in fine batiste or lawn. After early 1910, the cut of petticoats changed somewhat, becoming narrower overall, although still with some extra fullness at the back, to match the changing fashions of the day. The embellishment also changed -- broderie anglaise (eyelet embroidery) became as desirable as Valenciennes lace, even for the best lingerie. Toward 1916, crisp taffeta again became fashionable for day (and evening) wear under the widely-flounced skirts of that year. One-piece ‘combinations’, i.e. corset-cover-plus-petticoat garments (essentially equivalent to a full slip) became particularly popular after about 1910. These undergarments were offered in a wide variety of styles, along with petticoats, in mail order catalogues of the era. (See my discussion on these ‘combination slips’ further on). How to Wear: The Edwardian petticoat was normally put on over the corset, although (less frequently) might be worn under a corset that had no hose-supporters (garters). If your corset does have hose supporters, the petticoat must be worn over the corset (after fastening the garters to your stocking tops). Like the drawers, the petticoat should be pulled up into soft gathers at the back using the waist ties and tied into a secure bow at centre back. The buttons at back, if any, are then fastened, and the gathers adjusted evenly across the back, but concentrated in the centre. Typically only one petticoat was worn, especially in summer, although I have seen references to two petticoat layers, especially in the earlier years of the era. In the latter case, the first petticoat might be made of fine batiste and the second made of a fancy silk taffeta, satin, or sateen, with elaborate flounces. In any case, if you are planning to wear two petticoats, they should both be made of fine, lightweight materials to minimize bulk above hip level. Petticoats should be just slightly shorter than the outer skirt or dress, which is why it’s important to make or choose a reproduction petticoat that fits properly under your reproduction costume. A petticoat that is too long can be very easily shortened (in an historically accurate way) by making one or more horizontal tucks around the plain portion of the garment, just above or below knee level. Here is a selection of just some Edwardian petticoats from 1900 to 1918, as well as photos of extant petticoats in my own collection and reproduction petticoats made from 'History House' pattern #1903-A-002: 8. The Corset-Cover: This little piece of iconic Edwardian lingerie is self-explanatory -- it was always worn over the corset. It had a dual purpose: to enhance the “pouter-pigeon” shape, and to smooth out the visible top edges of the corset or mask the corset from view through sheer dresses. The corset-cover also prevented the corset’s busk from contact with the interior of bodices. Some versions of corset-covers had added frills or gathers across the front to fill out the bust area, and some were partially boned or in the shape of a bust-improver. The designs, styles, and embellishment of corset-covers was as limitless as those of petticoats. Certain corset-covers were intended to be almost visible, especially under the beautiful, semi-sheer silk, lawn or batiste summer "lingerie" dresses, and these were as pretty and lacy as the outer garments. Corset-covers intended for more practical wear under dresses or with walking suits were less lavishly endowed with lace, but still usually of fine batiste or percale. Even the most utilitarian corset-covers of the Edwardian era had their share of pretty lace edging and/or insertion, often combined with embroidery (after 1909 this tended to be broderie anglaise (eyelet) embroidery). Corset-covers were embellished with just as much attention as other fine lingerie, because (as mentioned above) they could often be slightly glimpsed through the semi-sheer lingerie blouses and dresses of the era. Corset-covers were often sold as a set with a matching petticoat. Most were constructed with a neckline similar to a chemise, i.e. an adjusting ribbon run through lace beading. Typically they closed at centre front with small buttons (usually mother-of-pearl). Corset-covers for evening or ball dresses were frequently designed with simple silk satin ribbons for shoulder straps that could be adjusted or pushed down off the shoulders as required. Some corset-covers doubled as bust-improvers as well, made with structural boning to further enhance a deficient figure. Usually a second corset-cover would not be worn over one of these dual-purpose undergarments. Changes with Time: This is the one piece of Edwardian lingerie that changed very little, and was worn throughout the entire 1898-1919 period (even though ‘combinations’ were often worn to replace the corset-cover-plus-petticoat arrangement). Accordingly, a pattern for a 1903 corset-cover (such as the ‘History House’ pattern shown below) can be worn with practically any reproduction ensemble up to about 1915/16. After those years, corset-covers did tend to become more streamlined and simpler, although fine quality corset-covers with lace and ribbon embellishment were still offered in catalogues in America as late as 1918 and 1919. How to Wear: The corset-cover is the last piece of Edwardian lingerie to be put on, over the corset (and bust improver or brassière, if any). It should be quite loose through the bust area but fit snugly around the waist. If you wear Edwardian dresses with open necklines, your corset-cover should preferably be cut to match the neckline (round or square). The gallery below presents examples of corset-covers through the first two decades of the 20th Century, demonstrating how varied and creative the design of this little piece of lingerie was: 9. Another ‘Combination’: Confusingly, both in French and English, the type of lingerie that combined chemise-plus-drawers, as well as the type that combined petticoat and corset-cover, were both referred to as “combinations” in the early 20th Century. I’ll use the term “combination slip” when referring to the latter type of undergarment here, to distinguish the two. This type of combination was the last layer of Edwardian lingerie put on, replacing the petticoat and corset-cover, designed along the same lines as those separate pieces, or sometimes in "princess" style. The general concept of a simple, one-piece slip-like undergarment had existed for some decades (at least as far back as the 1870’s). It was usually referred to in the late 19th century as an “under-dress” (‘robe de dessous’), and was typically cut with princess lines (i.e. no waist seam) that fit smoothly underneath the outer gown. However, the new Edwardian 'combination slip' was different -- it took the fashionable, existing styles of petticoat and corset-cover and amalgamated them at the waistline to create one, combined garment that could be worn in place of the two last pieces usually put on, creating a smoother line and simpler, more streamlined way of dressing. By about 1902-04, the ‘combination slip’, unlike its earlier antecedents that were simple princess under-dresses, was a true “combination” garment, cut and shaped in a similar way to the two parts it replaced. That is, the top portion was designed with the pigeon-breasted fullness of a corset-cover at lower front, and the skirt portion with all the usual flounces and frou-frou of a traditional petticoat. Judging from period magazines, advertisements and catalogues, these novelty two-in-one “replacement” undergarments seem to have been introduced sometime in the early years of the 20th Century, but only became frequently worn and generally fashionable after about 1907. The obvious reason may be that widely flounced petticoats and pigeon-breasted corset-covers were themselves novelties in the 1900-1907 period. And, like most fashion novelties, these 'combination slips' were more enthusiastically and readily adopted by younger women first. The standard petticoat+corset-cover sets continued to be offered in catalogues up to at least 1917. Princess-style combinations (really more like modern slips, without a waist seam, and usually called “princess petticoats”) also continued to exist throughout the Edwardian era, especially for “Empire” fashions popular around 1901, as well as after 1908 when a more sinuous, slender line was called for in outer garments. Like corset-covers, combination slips were made with different necklines to match outer garments that had open necklines. And like petticoats, they were available in a wide range of different materials, with enormous variation in lace trimming. Closures on these ‘combination slips’ varied, sometimes being centre front buttoning, sometimes with back button closing. Generally speaking, combination slips were more readily adopted by younger women, especially under summer gowns, along with a chemise+drawers combination, which greatly simplified and streamlined the toilette. Mature and older women tended to stick to their traditional 4-piece lingerie ensemble, as evidenced by advertisements and fashion articles of the time targeted toward women “of a certain age”. For use under formal evening or ball gowns (or bridal gowns), a full set of separate, traditional lingerie was still preferred, even as late as 1913. Changes Over Time: The ‘combination slip’, being an amalgam of petticoat and corset-cover, continued to be worn as long as the separate petticoat and corset-cover was. However, like their separate counterparts, the combination mirrored the fashions of the particular era. After about 1910, these combination slips, like their separate pieces, were pared down to more vertical, columnar lines. So for example, a combination of 1908 looks quite different in its silhouette from one of 1913. How to Wear: Like the petticoat and corset-cover which they replace, a combination of this type is the last piece of lingerie to be put on. If you choose to wear a combination slip, it should work well with the outline and intended silhouette of your outer gown or ensemble. Keep in mind that many women continued to wear the classic, 4-piece set of lingerie: chemise, drawers, petticoat and corset-cover throughout the Edwardian period, and these items were offered in mail-order catalogues of the time along with 'combination slips' and 'princess slips'. So you can choose which way you prefer to dress -- the latest, youthful under-fashions, or the traditional ones -- as long as the cut of the lingerie is appropriate to the cut of the outer garment(s). Below are some examples of the ‘combination slip’ type, from various years of the Edwardian period, showing the wide variation in these undergarments, including the “princess” slip form. The 'princess slip', that is, with a princess cut and no waist seam, seems to have been more prevalent in American catalogues than in Britain or Europe. I have yet to come across an actual photograph of a woman of this era wearing a 'combination slip', probably because it wasn't revealing enough to merit being the subject of "racy" sex-postcards of the time! 10. 'Ceintures' (or Shaping Belts/Girdles) An additional piece of lingerie, referred to by the French as "ceintures" (belts) [pronounced something like "san-tuer"], was advertised fairly regularly in fashion publications of about 1906 onward, although they may have existed earlier. Around late 1906 to early 1907 waistlines of gowns began to rise to an "empire" position (although not initially anywhere as high as in the ca. 1800 Empire era), and a long, lithe, youthfully smooth, but undulating silhouette became high style, as in the fashion plates below (from 1907). Presumably, for many women, corsets were just not enough to control all those undesirable bulges below the waist. These "ceintures" filled that need. These hidden undergarments were perhaps a bit too utilitarian to be considered strictly as "lingerie", and weren't actually corsets, but rather something akin to 1950's style "girdles" (without the power net, but often with boning). I like to call them "shaping belts", for that was their only real purpose: they were control garments, often (but not always) made of coutil, meant to provide additional reining-in of the female body below the waist. They took different forms, but generally included elastic garters for attaching to stocking tops. The following French advertisement makes it clear how these were worn -- under the corset but over the chemise, or else directly against the body, or even in place of a corset for leisure/at-home wear with an informal, déshabillé garment such as a morning robe. (Anything but allow the female form to escape!). The particular model shown below is described as being made of elasticized knitted material (likely silk or cotton). It promises that if worn directly against the body, it will "cause a progressive and sure slimming effect", while if worn over the chemise it will "prevent weight gain" and "facilitate the task of any corset in providing the narrow lower line (i.e. waist to hip line) so necessary for today's fashions". The advertisement further mentions that this article of lingerie has enjoyed a popularity beyond all expectation." A good example of early 20th century promotional pressure! Below are some further examples of these "shaping belts", showing differences in construction. The first image shows the front and back of a fully-adjustable model; the second image shows two separate models, one short and one long style. All three were intended to be made of sturdy coutil (unlike the more expensive tricot model in the advertisement above). In any event, these hidden body-shapers must have been in more widespread use by about 1908 than we realize: advertisements for them appear frequently in ladies' fashion magazines of the 1908 to 1910 period. After that point they seem to disappear, possibly because corsets themselves became much longer and served essentially the same purpose in one garment. It is noteworthy in this regard that from about 1910 onward, corsets more and more began to be made with garters included. 11. Miscellaneous Lingerie Items: The Edwardian era produced a fashion explosion of frilly, lacy, flouncy, frou-frou that applied not only to the unseen undergarments, but to a wide array of other items and accessories. These included everything from neckwear to parasols, handkerchiefs to reticules, fans, nightwear, blouse-waists and even outer dresses (called "lingerie" blouses and dresses). Everything was lavished with lace (especially Valenciennes insertion) and embroidery, preferably made from the finest batistes, lawns, and silks. Here I'll try to give a brief overview of these items that might also be thought of as "lingerie-extensions" or "lingerie-like". Items such as good quality nightgowns, peignoirs and combing jackets or matinées, while never worn outside the home, were lavished with as much care and decoration as true lingerie, and made of the same fine materials (usually batiste, but sometimes fine silks). Often these garments were sold as part of a trousseau, with lace embellishment matching that of the other lingerie pieces (chemise, drawers, petticoat, corset-cover) with which they were sold. Peignoirs or combing jackets were also sometimes sold with matching petticoat-skirts -- these ensembles would be worn in the morning while a lady was having her hair arranged for the day. Camisoles (in French, a long-sleeved, hip-length, front-closing morning jacket) were intended as temporary garments to be put on when one first arose in the morning. All these ancillary garments of any quality got the Edwardian lace and flounce treatment! Here are a few examples of fashionable nightgowns and peignoirs of the era. Additional accessories, such as jabots, fancy collars, fichus, and other neck wear could also be considered “lingerie” items. These were as fine and delicate as anything worn underneath, and were frequently lavished with expensive hand-made laces. It might also be said that the so-called “lingerie blouses” or “lingerie dresses”, which were constructed with the same attention as fancy undergarments (many even more so!), were actually an extension of them. These diaphanous garments were manufactured in such prodigious quantities, and so many have survived, that examples are still regularly offered for sale on the market today. Lingerie dresses were primarily worn in the warmer seasons, and the best of them were considered formal enough to be appropriate for such occasions as weddings, graduations, and garden parties. Particularly in the earlier years of the Edwardian era, the most beautiful lingerie dresses were made with a stunning array of laces, often hand-made, including incredibly beautiful examples of Irish crochet, as well as exquisite hand embroidery. Many of these garments and their embellishments were created by young immigrant women working in sweat-shop factory conditions (especially those from Ireland or the European continent, who had been trained by convents in the needle arts). This work was something that could no longer be duplicated in such quantity at low prices after WWI when regulations began to be enacted to protect workers. Lingerie blouses, unlike lingerie gowns, were worn practically all year round, especially under the jackets of walking suits, and were considered a necessary part of a fashionable wardrobe. Lingerie dresses and lingerie blouses were intended to be slightly transparent of course, so the lingerie worn under them needed to be carefully chosen to enhance and match the quality of the outer garment. This would generally mean all undergarments would need to be of fine, semi-sheer batiste or lawn, but the usual layers were still worn. An all-white toilette of this type was considered high style, appropriate even for more mature women. You can often see glimpses of the undergarments in photographs of lingerie dresses of the Edwardian era. Lingerie dresses were also frequently worn with either a white or pastel coloured, 'princess slip' type of undergarment immediately below. The pastel slip created a lovely transparent white-on-colour effect, a style considered most appropriate for young women or teenage girls. In these cases, the slip functioned as a sort of under-dress, and the chemise and drawers (or combinations) would still be worn underneath, as well as perhaps a white petticoat under the slip (for modesty's sake). These white or pastel-coloured "full slips" were separate items, not attached coloured linings in the modern sense. Below are just a few examples of lingerie dresses, including some photos showing the beautiful hand work and lace on some dresses in my own collection. Aprons were another item that, while not actually lingerie (in the sense of undergarments), were available in fine batiste, embellished with laces, for the lady of the house to wear while engaged in such genteel activities as serving tea to friends, arranging personal items in the parlour, or fetching herbs or flowers from the garden. These little garments were a world apart from the everyday, utilitarian aprons provided to household maids, and were often just as frilly and delicate as dressy lingerie, frequently trimmed with hand-made laces and/or embroidery. Here are three typical examples, two from 1905 and one from 1911: One unusual item of lingerie I’ve discovered in a 1912 department store catalogue was a 3-piece combination. This was described as a corset-cover type bodice attached to a combined skirt and knickers (actually very wide, long, flounced drawers looking like a skirt, but with the usual "open" crotch). This true "all-in-one" garment was, as with any other lingerie of the period, finished with tucks, frills, and laces. Not strictly speaking “lingerie”, a myriad of close-fitting, finely knitted undergarments were available during the Edwardian period, especially in colder climates. These included chemise/drawers ‘combinations’, sleeveless and short-sleeved vests, long-sleeved tops (corset-covers), and full-length suits (i.e. like modern long underwear), all available in various knitted materials such as wool, silk or cotton. These could be worn underneath the corset, next to the skin, or over top of the corset (as in the case of knitted corset-covers and vests). They resembled what we think of as “long underwear” or woollen underwear today more than the typical lingerie of the Edwardian era. In fact, these were plain, utilitarian undergarments, meant to provide necessary warmth, not beauty. Although you could probably still make these items today from materials like fine silk knit, (or even buy similar merino wool modern winter underwear), they are generally unnecessary for modern costume re-enactment, unless you plan to be outdoors for long periods in freezing weather. Below are just two examples of the wide array of finely knitted undergarments available, from catalogues of 1902 and 1909 respectively: Another example of “pseudo-lingerie” were the “plastrons” (fillers) that were intended to fill in the neckline of jackets (or occasionally dresses) with the appearance of a fine, lacy batiste or lawn blouse. These were often just as lovely as the lingerie worn underneath them. The examples below from 1907, heavily embellished with lace and embroidery, are typical: PART TWO: So What Do I Wear with Which Styles? As mentioned earlier, the outer line of fashion (the silhouette) did not remain the same throughout the ca. 1900 to 1919 time period. There were subtle but definite changes in certain years that need to be considered when planning undergarments. Choosing the right undergarments is an essential part of making your reproduction dress or ensemble look authentic. The corset-cover and chemise are more versatile and are appropriate over a longer range of years, whereas petticoats and drawers are more attuned to their particular outer fashions. Accordingly, here are some visual “galleries” giving you examples of silhouettes of outer garments in different periods during the 1900 to 1919 era, and showing which undergarments are best worn with them. I’ve also added a few notes on the particular features of each fashion period. Notice especially the lingerie pieces that are common to more than one period – these are the more versatile of the various undergarments. You can sew just one of these and use it for several fashion purposes over a span of years (items marked with an asterisk [*] are available as sewing patterns in my Etsy shop – see the button link below): 1. 1901 to 1906 The classic S-bend or "Gibson Girl" silhouette, with uni-bust, pigeon-breasted upper shape, small tilted waistline, and pronounced derrière. Sometimes two petticoats were worn, and taffeta outer petticoats (underskirts) were common, especially in cooler seasons. 2. 1907 to 1909 The "S-bend" silhouette is softened and streamlined by the influence of the "Empire" (high-waisted) silhouette, focusing on a more slender, sinuous line, especially in 1909, when the so-called "robes fourreaux" (sheath gowns) began to appear. The most fashionable undergarments for these "new" styles had to be chosen carefully to be as inconspicuous as possible. The best were made of fine, semi-sheer batiste or lawn, although the basic design of lingerie changed little from the previous years. Generally only one petticoat was now worn. Taffeta petticoats were still sold, but these were more often intended to be worn under tailored skirts and winter gowns during these particular years. Combinations (of both types) began to become more widely worn under daytime garments. Corsets were now a little longer in the torso, a little less exaggerated in design, and now regularly included elasticized garters (hose supporters). These also helped to pull the corset down smoothly on the body, helping to accentuate the graceful lines of the outer garment(s). 3. 1910 to 1914 By early 1910, a new aesthetic in fashion arose, a more columnar line with a much reduced volume of skirts below the knees (including "hobble" designs). These fashions began to demand more streamlined, slender undergarments with less widely-flounced lower portions. The change didn't happen overnight, and 1910 was a transition year. However by mid-1910, trained skirts with wide hems were no longer fashionable (although small, compact fishtail and square trains persisted in evening gowns). By the end of that year the vertical, columnar line was well established. The most vertical styles were seen through 1911 and 1912. By 1913/14 designers began to play with creative drapery and curved outlines, but the straighter, overall columnar line remained. The undergarments that are best for this whole period are slimmer, straighter, and less bulky, although you can still get away with ca. 1906-09 lingerie for most 1910 designs. Beyond that point, the outer garment should determine whether or not you need the "new", narrower undergarments. This is especially true of evening gowns of this era, which require the lightest-weight, finest, and most slender lingerie. For example, evening drawers and petticoats now clung very close to the natural form of the body. Chemises however changed little. The fabric of preference was fine batiste or lawn. Although the shape and cut of undergarments changed, many women still wore the classic 4-piece set of lingerie during the 1910-14 period. The large number of these items offered in mail-order catalogues of the time attests to their continued popularity. Of course, the newer 'combinations' of both types were widely sold as well. Corset-covers with boned shaping or ruffles also continued to be worn during the 1910-14 period to fill out the bosom of the less well-endowed, and 'brassières' of various kinds were becoming fashionable, particularly with the new lower-sitting corsets of 1912-14. But the large, exaggerated uni-bust "bust improvers" of the previous decade disappeared from mail-order catalogues and fashion advertisements of these years. The examples below show just a sampling of typical garments from mid-1910 through to late 1914, and the preferred types of undergarments to wear with these fashions. As you can see, there was a large array of options in fashionable lingerie during these years. 4. 1915 to early 1917 In 1915, skirts suddenly began to enlarge in volume again, this time falling in a wide, inverted cone shape. The tunic-skirts of 1914 became the tiered, A-line skirts of 1915. From mid-1916 onward, an raised waistline began to appear in the latest fashions. In 1916 especially, crisp taffeta dresses with flounces and ruffles became stylish. At the same time, hemlines rose slightly, to around or just above ankle length. The trained or hobbled skirts of the previous decade disappeared; they were no longer practical for the average woman, coping with running a household (especially during war time) with few if any servants to assist. Probably as a result, most dresses of this time period (unlike previous years) were front- or side-fastening so they could be put on by the wearer herself without help. Undergarments changed accordingly. Although a chemise and separate drawers were still the classic pieces, women were often adopting "combinations" (chemise plus drawers) instead. These were becoming more and more slim and pared down. By 1917, the so-called "envelope chemises", essentially a short combination with a loose, snap-fastening crotch, were being offered in a variety of styles. The new corsets, on the other hand, sat low on the torso, most of them completely below the bust, making a brassière a desirable addition to the lingerie ensemble. Corsets were now focused on creating a smooth line from bust through lower hip, rather than an hourglass figure with a tiny waist. New materials such as rust-proof aluminum boning, elasticized panels and tricot fabrics were now being featured in corsets, and front lacing models were available, allowing a woman to put her corset on without assistance. All these innovations offered convenience and greater comfort. Petticoats, after having been "deflated" to match the columnar styles of 1910-14, needed to be wide and flouncy again, to enhance the outer skirts of 1915 to early 1917. Taffeta or taffeta-like substitutes, were especially popular for petticoats of these years, as they gave extra loft and bounce to the costume. In fact, petticoats of 1915 to early 1917 looked remarkably like those of 1900-04, the main difference being the shorter length of the later styles. If you're planning a reproduction wardrobe of these years, it's important to choose the proper undergarments to support and enhance the outer fashions. This is especially true of the petticoat. Much like the 1950's, the fashions particularly of 1916, need the extra body provided by a crisp, flounced petticoat. 5. Mid-1917 to 1919 By the middle of 1917, fashion began to discard its brief fling with wide, flouncy, feminine skirts. Skirt silhouettes deflated quickly, and by late 1917 the fashionable line was slim, straight, shorter, and non-fussy -- recognizably modern. It's reasonable to assume that wartime had at least some part to play in that change. Certainly far less fabric was required for these more or less straight skirts than for the confections of 1916. In addition, there was a brief fashion for barrel-shaped skirts (which the French called "boule"), with either rounded hip or hem silhouette. These were nonetheless slim-line skirts and dresses that required slimmer, less voluminous lingerie underneath. During these 'transitional' years to the 1920's, lingerie's starring role in the wardrobe faded. For the fashions of 1918 and 1919 especially, a sleek simplicity and practicality became important. This didn't mean that lingerie no longer had any embellishment at all -- the better quality items still sported lace and embroidery -- but the days of profuse, exorbitant use of metres upon metres of lace and extensive hand embroidery on undergarments were gone. The chemise, however, was the one garment that remained more or less consistent, except for its shorter length. That is, for women who chose to stick with the old habit of chemise-plus-corset-plus drawers, rather than wearing one of now common envelope chemises, combinations, or slips. As a result, a chemise of 1903 could still be worn (if shortened) with any style up to 1919. Drawers themselves were now little more than lightweight, straight-legged "shorts" with a snap crotch closure. Corset-covers changed relatively little, but 'combination slips' (what we would call 'full slips') were a common replacement for the petticoat-plus-corset cover arrangement. Since a vestige of the "uni-bust" (or pigeon-breasted) silhouette remained, even by 1918, corset-covers were still being sold with extra ruffles at front to fill out the bust area. Petticoats were slimmer and less fussy than they had ever been, although of all the separate lingerie pieces, they were the most likely to receive generous lace embellishment, often by this time machine-made. Crisp, springy taffeta once again gave way to materials with less stiffness and body (such as crêpe de Chine). Batistes and lawns continued to be fashionable and widely available. By the end of 1919, when women's skirts, dresses and suits were cut basically straight up and down, and the dropped waistline began to appear, the transition to the modern lingerie "uniform" of bra, panties and slip was all but complete. A Few Final Thoughts Where early to mid-Edwardian lingerie was concerned, there was almost no limit to how extravagantly delicate and lacy these items could be. What had for centuries been fairly practical women’s undergarments had suddenly become the hidden star of a wardrobe. (The question of why so much attention and expense was lavished on unseen female undergarments is a fascinating one, but better left to psychology and social science!). Even moderately well-to-do women of the Edwardian era had several sets of lingerie; the wealthier had dozens of each type, for every possible occasion. Most of these items could be laundered, but anyone who could afford it would regularly buy new lingerie to replace older or outdated pieces, especially when buying via mail-order catalogues became more widely available. The fact that this beautifully-made lingerie was priced within reasonable reach of the middle-class meant that vast numbers (certainly millions) of these pieces were being produced every year to satisfy the feverish market for fancy underthings -- the main reason so many “Edwardian whites” still survive today. Typical fine quality petticoats cost between about $1.50 and $2.50 in 1912 in Canada, equivalent to the cost of a nice pair of shoes or boots at the time, something the average household with even modest means could afford once in a while. This gives us a fair comparison to today’s monetary values. All this frilly production did come at a price though. Thousands upon thousands of poor, young immigrant women who came to North America were hired to work in production factories in big cities at near-starvation wages and often in dangerous conditions to meet the ongoing demand. However, once these young women began to be needed for other jobs at the outbreak of WWI, everything began to change – including the making and wearing of extravagant lingerie. So if you’re fortunate enough to own a piece of true Edwardian lingerie, treasure it, and think of the incredible skills of the young women or teenage girls who laboured 14 to 16 hours a day, 6 days a week, to produce such a beautiful piece. On the other hand, today it’s possible for home sewists to replicate this lingerie (to a degree), although admittedly it’s a time-consuming project, and not inexpensive if done with the proper materials. Fine cotton batiste is still available these days (the finest and most beautiful is Swiss-made), as are the traditional Valenciennes insertions and edging laces, and I highly recommend these for your reproduction lingerie. Patterns in the ‘History House’ line are taken directly from French originals, allowing you to almost exactly replicate the beautiful lingerie of the Edwardian era. A full complement of lingerie pieces from 1903 and 1904 is available in digital format sewing patterns in my Etsy shop. I also offer a typical 1912 “combination slip” style, perfect for the latter years of about 1910-14. Made in good quality cotton batiste with even a small amount of lace embellishment, these pieces are perfect for any Edwardian wardrobe. Constructed of the finest Swiss batiste, with true Valenciennes lace insertion and quality lace edging, they can be heirloom pieces, fit for a 21st century historically-themed wedding. Although some of these items do require good, careful sewing skills, none is beyond the capability of a moderately experienced sewist. Here is the link to purchase sewing patterns for some of the pieces pictured in this article: Have Fun!

I love making (and wearing) lovely, lacy, semi-sheer reproduction Edwardian underthings, and I think you will too! I also hope this article will be of some help in deciding what and how to wear your reproduction Edwardian lingerie.

15 Comments

Rita Parisi

19/12/2019 07:47:03 pm

Thank you Patricia for this great article. I've been portraying a fictional character from 1908 for 15 years now. Years ago, I had to dig around A LOT to find info on lingerie from the year. It was a cusp year as far as fashion goes and is the reason I chose that year to portray. After reading your article, I'm glad to know that I got the lingerie aspect right but I still learned so much. For example: I didn't know they were still using whale baleen for corsets in 1908. Also thank you for clarifying what a Union Suit is. Came across this in my 1908 Sears and Roebuck catalogue and thought it might be long underwear but still wasn't sure until I read your article. :)

Reply

The Fashion Archaeologist

20/12/2019 05:13:53 pm

Thank you Rita, I'm glad it was of help!

Reply

20/12/2019 01:25:18 am

What a wonderfully comprehensive and researched article! I appreciate you sharing your time and expertise with us. It did answer one particular question I've had, which is what is worn under lingerie gowns. My guess would have been for simpler lingerie so as not to take away or distract from the outer gown, but apparently that was not the thinking! (No one ever said fashion had to make sense...)

Reply

The Fashion Archaeologist

20/12/2019 05:22:57 pm

I'm so glad you found this useful and interesting, thanks so much!

Reply

Black Tulip

21/12/2019 06:47:53 pm

Thank you for such an interesting and detailed article.

Reply

Anonymous

12/9/2021 03:06:12 pm

I love how detailed this article is! I was confused by the different pieces, the order of things wore, and the changing silhouettes, but you made it so comprehensible and organized. Thank you!

Reply

17/9/2021 04:19:51 pm

Dear Fashion Archaeologist,

Reply

18/9/2021 03:48:40 pm

Many thanks for your comments, I'm so glad this information was helpful!

Reply

19/9/2021 04:04:56 pm

Dear Patricia,

Kiwi

3/8/2023 04:09:04 am

This was really intresting! Would most of the undergarments be the same for the victorian era?

Reply

Tara

24/4/2024 09:47:55 am

Hi! This article was extremely useful. I'm 17 and I'm going to be making a lingerie dress and lingerie from the edwardian period for a school assignment. It's so difficult to find a website that explains it all. I'm so glad I found this since it made a lot of things clear. I really want to make a chemise because I like it more than the chemise+drawers combinations but till when does the chemise get worn? Also, are there any very clear differences in lingerie dresses specifically throughout the years? I want to make a historically accurate dress but I have an idea about what kind of dress I want to make and I just don't know in which year they wore lingerie dresses like the one I want to make. I need to know the year to make the lingerie that fits with the dress, time-wise spoken. I was wondering whether you could help me with that since it's hard to find clear answers online. Thank you again for the amazing article!

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorPatricia Preston ('The Fashion Archaeologist'), Linguist, historian, translator, pattern-maker, former museum professional, and lover of all things costume history. Categories

All

Timeline

March 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed